The Destiny of the French Peasantry

by John Rhys

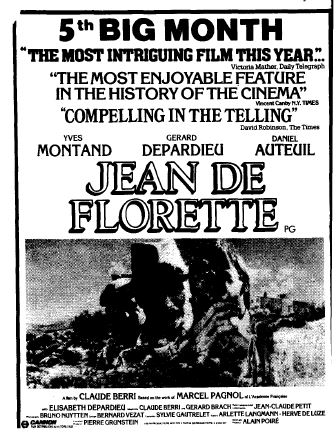

- Jean de Florette

- Manon des Sources

- The twist of fate

- Missing the point

- The Church v. the Peasantry

- The Absence of the Left

Jean de Florette and Manon des Sources are being shown separately in London cinemas but they are really two parts of the same film. At the end of Jean de Florette, there is a sub-title saying “End of Part One”, and neither film is comprehensible on its own. The significance of the action of Jean de Florette is made clear only at the end of Manon des Sources and the plot of Manon des Sources represents the resolution of the action of the first film and is unintelligible to someone who has not seen the first film.

It is an act of great cynicism on the part of the distributors to show them as separate films. This undoubtedly maximises the return to be made on showing them. But it expresses an intense contempt for the public, as well as for the idea of the integrity of a work of art. And the films have certainly been received by the critics as works of art. While letting the public down by failing to censure the distributors for their cynicism, the critics have heaped praise of the most flowery kind upon both films.

This wholly uncritical response on the part of the professional film critics is an index of the degree of disorientation which now characterises the British literati in general. Not a single reviewer, with the exception of a very half-hearted Alexander Walker in the London Evening Standard (November 19, 1987), has discussed the meaning of these films. Yet their meaning is unmistakeable.

Jean de Florette

Jean de Florette describes how two peasants in the Provence of the 1920s get hold of a valuable water source. Ugolin returns from military service with the idea of growing carnations on a commercial basis. His uncle, Papet, who is as cunning as Ugolin is naive, realises that Ugolin’s land lacks sufficient water and tries to buy land containing an important source from an unfriendly neighbour. In an argument, the neighbour falls and dies and the land reverts to his relative, a woman called Florette whom Papet had once known before she moved from the locality. But Florette is now dead and it is her son, a hunchback called Jean, who arrives with his wife and child to make a new life on the land, abandoning his job as a tax collector in town to try his hand at raising rabbits for sale, armed with the latest scientific theories and techniques and unlimited determination.

But he does not know about the source and Papet and Ugolin have taken care to block it up before he arrives. They assume that he will soon give up his bucolic dream when the summer drought puts paid to his plans. But they underestimate Jean’s determination and, by withholding the information he needs, become passively implicated in his eventual death. In his desperate search for water, Jean uses dynamite to sink a well and is killed by a flying rock. Papet and Ugolin buy out his widow and joyfully unblock the source, unaware that they are being observed by Jean’s daughter, Manon. Here the first film ends.

Manon des Sources

The action of Manon des Sources takes place about ten years later. Jean’s widow is pursuing her old career as an opera singer in the city, but Manon, now aged about eighteen, is still living in the area, working as a shepherdess for a local peasant woman, and apparently wa1tmg for an opportunity to settle accounts with the men whom she holds responsible for her father’s death. Ugolin is prospering as a carnation grower but is still unmarried. Papet, himself a bachelor and acutely aware that he and his nephew are the last of the Soubeyran family, encourages him to find a wife. Ugolin falls in love with Manon, unaware that she knows the truth about the water source. She repulses his advances with contempt and falls in love instead with a young schoolteacher.

Discovering by accident the source of the village’s water supply, Manon blocks it up and thereby brings matters to a head. The villagers had always known about the source which the Soubeyrans had blocked up but, in deference to peasant traditions, had not intervened in the affair to tell Jean de Florette about it, because he was not a local man and there had long been a local animus against his mother for moving away and marrying into another locality. They are therefore implicated in his death. The stopping of their water supply threatens them all with ruin and brings the Church into the act, interpreting it as an act of God to punish the community for its collective treatment of Jean.

Discovering by accident the source of the village’s water supply, Manon blocks it up and thereby brings matters to a head. The villagers had always known about the source which the Soubeyrans had blocked up but, in deference to peasant traditions, had not intervened in the affair to tell Jean de Florette about it, because he was not a local man and there had long been a local animus against his mother for moving away and marrying into another locality. They are therefore implicated in his death. The stopping of their water supply threatens them all with ruin and brings the Church into the act, interpreting it as an act of God to punish the community for its collective treatment of Jean.

The climax comes when Ugolin acknowledges Manon’s loathing for him and her love for the teacher and, unable to live with this knowledge, seals the doom of the Soubeyrans by hanging himself. Manon and the teacher unblock the source and the water flows again at precisely the moment the Church is organising a procession around the village fountain praying for a miracle. Papet, a broken man, visits his nephew’s grave while Manon marries the teacher. Finally, he – and we – learn from an old woman the truth about Jean de Florette.

The twist of fate

Florette had been Papet’s lover decades earlier and had written to him when he was in North Africa with the army to tell him that she was pregnant but would bear his baby if she could tell the village that she was his fiancee. Papet had never replied, so to hide her shame she had left the village, married another man and borne the child. A hunchback. In other words, Jean de Florette was Papet’s son and Manon is his granddaughter. Papet had devoted all his cunning to ruining Jean in, order to promote his nephew and thereby preserve the line of the Soubeyrans, when Jean was a Soubeyran all the time and a truer Soubeyran, with all his father’s tenacity and resourcefulness, than the pathetic Ugolin.

The old woman who tells Papet this upbraids him as an evil man who deserves everything that has come to him. She assumes that he had deliberately left the pregnant Florette in the lurch. But Papet had never received Florette’s letter. The army had been constantly on the move and mail frequently failed to get through. He had had no idea that Florette was pregnant and had always felt bitter since discovering on his return from the army that she had moved away and married someone else. In other words, the entire plot of the film (i.e. of the two films taken together) follows from a twist of fate, the failure of Florette’s letter to reach Papet in North Africa.

Missing the point

The critics have praised the films as a satisfying story of righteous revenge, of guilt justly punished. This is a total travesty of the meaning of the films. The fact that Manon does nothing whatever apart from blocking up the village water source is enough to refute the notion that the second film is a story of revenge. Nor is its theme the punishment of guilt. It is the triumph of fate. Verdi’s “Force of Destiny” provides the theme music. The centrality of the theme is made explicit in the key exchange between the pathetic Ugolin and his wilful scheming uncle: Ugolin, resentful of Papet’s constant prompting, invokes destiny, only to provoke Papet’s furious reply: there is no such thing as destiny, destiny is the excuse of the weak-willed.

The actions for which Papet and Ugolin are ‘punished’ are not crimes. In aspiring to get hold of Jean’s land and water they have broken no law. They are simply peasants seeking to further their own normal interests. Jean’s death, like that of the previous owner, is an accident which they do not foresee let alone premeditate. Their only questionable action is to block up the source in the first place and to keep quiet about it thereafter – a piece of peasant cunning and unscrupulousness which is utterly banal in its normality.

In suggesting that Papet and Ugolin are punished for outrageously immoral behaviour, English critics have entirely missed the point. Their story is certainly a morality tale, but it is the mores of the French peasantry in general which are at issue.

Crucial to the meaning of the films is the fact that Papet and Ugolin are entirely typical peasants, representing between them the entire gamut of the peasant character as this is conceived in urban stereotypes – Ugolin the peasant’s stupidity and avarice and pathetic desire to get ahead, Papet the other side of the coin, peasant cunning and the desire to perpetuate the family line. The films tell the story of their defeat by more powerful forces, Destiny, that is, the will of God, which reduces all their endeavours and plans to nought and, in Papet’s case, not only destroys everything he has worked to achieve but confronts him, when he is finally a broken man, with knowledge which reduces his entire life to meaninglessness.

The Church v. the Peasantry

This does not exhaust the meaning of the story, however. The force of destiny, God’s will, has this-worldly representatives. Jean de Florette is a townsman. Manon, his daughter, is also a townswoman; she lives as a shepherdess only until she can come once more into her own and in marrying the school-teacher she reverts to her social station. And the social institution which appropriates the victory of destiny is the Catholic Church, the vehicle of an ideology profoundly hostile to the introverted ethic of solidarity of the peasant community and the wilful individualism of its members.

Jean de Florette and Manon des Sources are about the defeat of the French peasantry by urban France and its Church. The story takes it for granted that the urban middle class (the class of tax collectors and opera singers and school teachers) represents civilisation and that peasant society is primitive and amoral. But the victory of French bourgeois society is mediated by the victory of its Church. The scientific aspect of urban civilisation is depicted as useless in the campaign against peasant society.

Jean de Florette’s scientific techniques avail him nothing since God is not on his side, and the expert from the Water Department called in by the Mayor after the water supply has dried up is shown to be hopelessly incapable of dealing with angry peasants and is a figure of ridicule.

The victory of the Church is the victory of an ideology which stresses the vanity of human action and human will. The defeat of the Soubeyrans -Jean de Florette every bit as much as his father and cousin – is the defeat of the human qualities of individual will power and entirely natural ambition. The ideology of these films is the extreme fatalism of Catholic doctrine, a doctrine profoundly opposed to the concepts of human responsibility and individual guilt or virtue. It is the ideology which the forces of democracy and socialism in France have been struggling against for two hundred years.

The Absence of the Left

Within a decade of the action of Manon des Sources, France was under German occupation and the Vatican was in virtual alliance with the Nazis and their scheme for a new, fascist, order in Europe. And the densely woven solidarity of the peasant community and the tenacity and resourcefulness of its members were the human bedrock of the French Resistance. But in furnishing the human basis of the Resistance, rural France was organised and given a collective sense of purpose by an aspect of urban France of which no mention is made in these films, the Left, the French Socialist Party and, above all, the Communist Party, the 20th century heirs of 19th century Republicanism and its passionately anti-clerical outlook.

It is, at first sight, astonishing that these films should have been made in France in the 1980s and that the principal role, that of Papet, should have been played by Yves Montand. Throughout his career, Montand has flaunted his left-wing credentials. The star of Alain Resnais’s La Guerre est Finie (1966), in which he played a leader of the Spanish anti-Franco underground in exile, and of Costa Gavras’s Z (1969), in which he played the Greek leftwing politician Lambrakis assassinated in 1963, Montand has gloried in his status as a fellow-traveller of the French Communist Party. But since its catastrophic showing in the 1981 presidential election, the terminal decline of the PCF has been plain for all to see, and its capacity to orient artistic activity in France has clearly suffered a corresponding decline. So much for left wing film stars.

None of this explains or excuses the reception which Jean de Florette and Manon des Sources have had over here. It speaks volumes for the mindlessness and lack of philosophical bearings of the contemporary London intelligentsia that these reactionary films should be universally praised and should be playing to packed houses.

This article appeared in January 1988, in Issue 5 of Labour and Trade Union Review, now Labour Affairs. One of many on the website. See https://labouraffairsmagazine.com/very-old-issues-images/magazine-001-to-010/magazine-005/.