Gorbachev: How to Wreck Everything and Be Loved by Your Country’s Enemies

by Gwydion M Williams

This article first appeared in May 2018, in issue 34 of the magazine Problems.

To Subscribe, go to the Athol Books Webpage

A man takes over a sluggish old multinational company. He announces dynamic changes, but nothing much comes of it. He is ousted in a boardroom coup, caught between two rival factions. Parts of the company are sold off, and the assessed value of the rest drops. In the following years, employees have to endure wage cuts and lose their pension rights. And some slick twisters become rich amidst the ruins. The man was a fool unable to turn good intentions into reality, right?

Wrong in the case of Gorbachev, and Yeltsin after him. Or so say the Western media, which just coincidentally are mostly owned by a narrow more-than-millionaire class that did very nicely out of the wreck of the Soviet Union. Did even better in the wider world, when the Soviet collapse of 1989-91 demoralised left-wingers.

The drastic crisis in the West in 1987 was forgotten. The evaporation of their main for boosted the confidence and popularity of the New Right. Made their rivals uncertain.

The shift has been so gigantic that apparent critics like Piketty assure everyone that it is a complete coincidence that a vast gain in income by the richest 1% coincided with a big shift rightwards in economic thinking.

Note also that this rightward shift happened only on economic matters. Socially, ideas once confined to the radical left have now become mainstream. Thatcher almost certainly believed that ‘economic liberty’ would cause a restoration of the old-fashioned values that she fondly supposed to be normal. John Major apparently believed the same, but was ready to be moderate on economic matters. Sadly, he also failed on economic matters, burdened by Tory factions who blamed the European Union for all of their ills. But Tony Blair clearly took the Soviet collapse to mean a failure of socialism. He applied New Right economics to new areas, most notably the National Health Service, which Thatcher had feared to touch.

Blair failed to notice that the promised improvements had not happened. He overlooked that the world’s most successful economies had hung onto the corporatist and interventionist systems that the New Right hated and New Labour no longer defended.

This brief consensus of New Right and ‘New Labour’ managed to tap into the confused feelings of both the Baby Boomers and the generation that had grown up since. Freedom was good and the state was at best an unavoidable evil. The informal ‘social contract’ that the rich now accepted could be summarised as:

‘You do as you please, while we grab more and more of the economy. We bias thinking in our direction by media that needs vast investments and is then often given away free. But we will give you the same freedom in private life that the ruling class has always enjoyed covertly. This is not so generous: we no longer have to hide whatever some of us are.’

For a while, New Labour seemed to work. The Tories had a run of bald-headed, offensive, and unpopular leaders: William Hague till 2001; Iain Duncan Smith till 2003; Michael Howard till 2005. And then they got David Cameron. Cameron made the Tories electable by conceding that they were not a party of old-fashioned values. Radical changes like Gay Marriage were made Tory policy, along with the absurd claim that this was actually conservative. But New Right economics, though substandard for the society as a whole, had been a grand feast for a more-than-millionaire class that dominated the Tory Party. And the ignominious collapse of the Soviet Union under Gorbachev was still seen as a big argument in favour.

This is a review of a review. Specifically, of Big Man Walking, by Neal Ascherson.[A] My take of his review of Gorbachev: His Life and Times by William Taubman.[B] The review is mostly what one would expect from a mainstream Western writer: but bits of reality do break through.

“The Congress of People’s Deputies, the new parliament of the Soviet Union, was in session and we were hearing its elected members voting freely, unpredictably, without fear. The voice – strong, lively – belonged to the man in the chair, Mikhail Gorbachev.”

And produced an outcome flatly against what any voter would have wished for. A result very different from the promises made by the candidates. But a result that should have been the expected outcome of their foolish policies.

Open elections give the public a chance to vote in fools and liars, and they very often take it. Autocratic parties have a much better record of delivering what they promise. It helps that autocrats cannot easily blame anyone else, in the way elected politicians tend to do. The main attempt to do so ended badly:

“In 1956, Khrushchev launched serious ‘de-Stalinisation’ with his famous denunciation of Stalin’s crimes at the 20th Party Congress. The speech electrified the outside world, but went down badly in places like Stavropol. The local party accepted the new line, as they had to, but were unable to understand it. A district secretary told Gorbachev: ‘I’ll be frank with you … the people just refuse to accept the condemnation of the personality cult.’ Many peasants were dismayed by the condemnation of the rural Terror; for them, the purge had ‘liquidated’ the hated collective farm bosses who had seized their land in the first place. When men came to remove the statue of Stalin in Stavropol, a crowd tried to stop them.”

Khrushchev claimed the right to rewrite history, without any public debate. Very different from China, where there was a limited relaxation in attitudes to Mao after his death.

Both Mao and Stalin remain popular – Stalin’s popularity has risen steadily as Russia continues to lose ground. This confuses Western writers, who usually get slippery when ‘the people’s choice’ is something they don’t approve of.

“Andropov was well aware that the Soviet system was seizing up: he and Gorbachev could agree on that. But he suffered from a ‘Hungarian complex’: the conviction that reform from below would inevitably burst out of control, as – in his view – it had done in Czechoslovakia. Asked about human rights, as defined in the Helsinki Accords which he had somehow persuaded Brezhnev to sign, Andropov remarked that ‘in 15 to 20 years, we will be able to allow ourselves what the West allows itself now, freedom of opinion and information, diversity in society and in art. But only in 15 to 20 years, after we’re able to raise the population’s living standards.’

“Every so often Taubman’s book halts, and unleashes a jostling, barking pack of questions. Most have real bite. Why did Gorbachev do this, why didn’t he do that, when a different decision might have avoided a defeat or hastened progress? But the question raised by Andropov is one of the biggest, and now overshadows all reflections on Gorbachev’s six years in power. Deng Xiaoping in China was to share broadly the same priorities as Andropov: let us first build an economy that works, enriching both state and people – and only then turn towards political transformation (some day, if we feel it’s safe). So why did Gorbachev do the opposite after he reached the leadership in 1985? No perestroika without glasnost: he was convinced that free, uncensored discussion was the precondition for breaking down massive resistance to economic reform, not the outcome. And China was not Russia: the Chinese Communist Party could call on traditions of obedience and discipline that were already disintegrating in the USSR after Stalin.”

He leaves out that there was still a strong popular will for some form of socialism in Czechoslovakia. It is likely that had the late-1960s reform succeeded, Libertarian ideas would have remained a marginal creed of the Hard Right.

***

“Why didn’t he [Gorbachev] launch a crash programme for consumer goods, why didn’t he go straight into economic reform, why didn’t he privatise agriculture? Instead, he went back to reading Lenin to discover where the Soviet system had gone wrong (revisionist communists all over Europe were doing the same), and decreed an anti-alcohol campaign that ended in painful failure. His grand plan for ‘accelerating’ industry, rather than introducing market forces, slowly fizzled out in a welter of shortages and official lies. Gorbachev hurled himself about the land, urging managers to adjust their minds to new thoughts. ‘Can’t you see that socialism itself is in danger?’”

The reviewer is another victim of the delusion that there was some strong difference between Lenin’s creation of the system and Stalin’s successful continuation. I’d assume the book would not mention that Lenin decided to ignore the Constituent Assembly, in which socialists had a 9-to-1 majority, but only 1 in 4 had Bolshevik coherence and determination. And that Lenin later banned all possible opposition.

“The media used their freedom under glasnost to attack Gorbachev on both fronts: either for throwing away all that had been won by the sacrifices of the Soviet people, or for hesitating to smash down the bastions of the Soviet system itself. For a silent but increasingly hate-filled majority in the party’s guiding bodies, the familiar world was ending. For the Russian people, especially, chaos and shortages were becoming reasons to turn against Gorbachev, whose popularity rapidly shrank in the course of 1990.”

Gorbachev had released political forces that pulled in different directions. This made real change impossible while he tried to keep a balance. One of several alternatives had to dominate, to get anything done.

“When Gorbachev backed away from the ambitious ‘500 Days’ plan for conversion to a market economy, drawn up by his brightest advisers, Yeltsin said that he had missed his ‘last chance for a civilised transition to a new order’.”

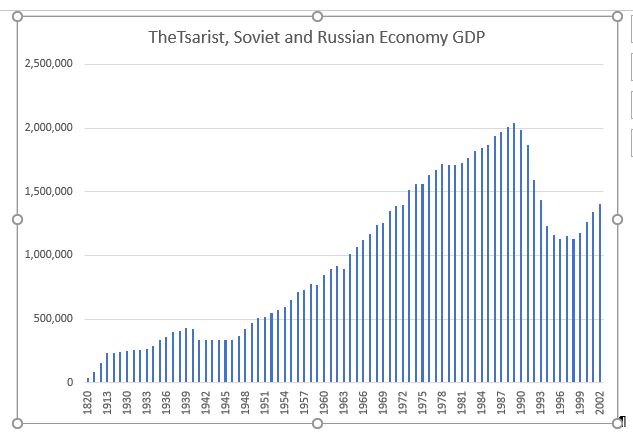

I’d suppose this was similar to what Yeltsin later did. A formula for shrinking the economy and turning over much of it to tricksters and gangsters, which is what Yeltsin later delivered. Which Putin got under control, but the same process continues in Ukraine. This potentially rich country has been ruined by lousy politics, with its weaknesses only encouraged by the two Orange Revolutions sponsored by Western governments.

The West could have helped the former Soviet Union, but preferred to inflict New Right foolishness on them. They may have genuinely believed their Free Market rules would do good. But can hardly have failed to realise that Russia was being cheated and betrayed when it came to Power-Politics:

“Gorbachev was also coping with the enormous new question of Germany’s future. The West, including Chancellor Kohl, assumed that he would oppose German reunification, but he accepted it. Then they thought that he would probably refuse to allow a united Germany to remain in Nato, and would certainly veto the extension of Nato into what had been East Germany. But in May he came to Washington and suddenly agreed with Bush that ‘united Germany … would decide on its own which alliance she would be a member of.’ The Americans couldn’t believe what they were hearing. Gorbachev’s own staff were thunderstruck…

“Though Taubman doesn’t put it like this, the West took Gorbachev’s co-operation for weakness. He expected an economic and financial reward for his concessions: it didn’t come. Crucially, in February 1990, James Baker, the US secretary of state, and Chancellor Kohl assured Gorbachev that Nato wouldn’t expand eastwards, certainly not towards the Soviet frontiers. But Gorbachev failed to make them write it down and Bush later told Kohl that he and Baker had gone too far. ‘To hell with that! We prevailed. They didn’t. We can’t let the Soviets clutch victory from the jaws of defeat.’ A few years later, by 2004, all the ex-Warsaw Pact nations, including the Baltic republics and Poland, had been brought into Nato. After their triumphant experience with Gorbachev, Western leaders reckoned that they could get away with it. But the ‘broken promise’ grievance smoulders under Putin’s European policy to this day. Most Russians, whatever their view of Putin’s autocracy, still look on Nato’s surge up to their borders as the treacherous breach of an international agreement.”

It was indeed unbelievably foolish, and Russians resent it still.[C] Gorbachev seems to have taken Western propaganda at face value and think it was ‘all sweetness and light’.

On the specific issue of NATO, the West in 1989 would have been delighted with an agreement that Poland etc. should become officially neutral, as Austria was when the Soviets withdrew. That could have been made a binding. Something written clearly and simply enough that even the lawyers who dominate US politics could not have wriggled round it.

How Gorbachev missed it is hard to see. I’d suppose the Soviet system encouraged a lot of mutual trust, and some people switched that trust to the West.

***

“The coup took place on 18 August 1991. Gorbachev, Raisa and their family were in their Crimean villa when it was surrounded by armed men. Announcing that the president had been taken ill, the plotters proclaimed that they had taken control of the Soviet Union as a State Committee on Emergency Rule…

“Why did the coup fail? Taubman’s account confirms the incredible bungling of the plotters, who almost from the outset seemed terrified by their own audacity. But they had a chance. I was there, and saw how – outside Moscow and Leningrad – ordinary people and local apparatchiks instantly accepted that the perestroika holiday was over: it was back to censorship, silence and the ‘normal’ post-Stalinist grind. A friend of mine said afterwards: ‘A handful of good, brave people saved Russia.’ I like to believe that she was right. The plotters’ worst and ultimately suicidal error was failing to arrest Yeltsin. But before he even arrived at the National Parliament building, mounted a tank and famously roared defiance, ‘good, brave people’ were already barricading the building. A line of women linked hands across the Kalinin Bridge, proposing to stop the tanks of the Taman armoured division. ‘We are mothers!’…

“There was a moment – perhaps 36 hours – when the conspiracy controlled the army and murderous ‘special forces’ and could easily have drowned opposition in blood before it had time to spread. They faltered while the ‘handful’ became a human sea, then they collapsed. Several plotters flew to Crimea to whine for Gorbachev’s pardon, but Yeltsin’s men were soon on their way in their own plane to free Gorbachev and arrest them.”

I don’t suppose the book mentions the contrast between what the Chinese did in June 1989. Western experts don’t trust the readers to remain ‘good-thinkers’ if it were made clear that the Tiananmen Square crack-down was a Leninist system fighting for simple survival.[D]

They might also not remain ‘good-thinkers’ if the contemplated the way Russia sank rapidly until Putin took over, while China continues to rise.

“From the moment of the coup’s failure, Yeltsin and his team were effectively running not only Russia but all that was left of the Soviet Union. It took Gorbachev a long time to realise it…

“Gorbachev was jeered as he addressed the Russian supreme court. And when he claimed that the Soviet cabinet had resisted the coup, Yeltsin thrust in his face a paper showing that almost all of his ministers had gone along with it…

“He spent the next months negotiating towards a new ‘union treaty’, granting the Soviet republics wide autonomy. But Ukraine refused to take part, heading for full independence, and in November Yeltsin suddenly vetoed any Russian participation in the treaty. A few weeks later, he went behind Gorbachev’s back and – at a secret meeting in a Belorussian forest – set up the Commonwealth of Independent States with the leaders of Belarus and Ukraine. The Soviet Union was over. So was Gorbachev’s power. He made his televised resignation speech in the Kremlin on 25 December 1991. Yeltsin switched off his own screen halfway through, and sent two colonels to take the ‘nuclear briefcase’ from Gorbachev and bring it to his own office.”

Yeltsin was the worst individual failure in Russian history: a man whose active policies did damage that no foreign foe would have dared try. Other bad rulers merely failed to keep control or make necessary changes – most notably that ignorant little anti-Semite, Tsar Nicholas the Second. A man whose inaction authorised pogroms and also massacres of ethnic-Russian protestors who were initially very loyal. A man who favoured a jumble of mad mystical ideas collected under his rule as The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. And now made a Saint by the Orthodox Church: that is how absurd post-Leninist Russia has become.

It was also tragic for Ukraine that it became sovereign, rather than being locked into some better Federal structure than the meaningless ‘Commonwealth of Independent States’. It was always likely from 1991 onwards that it would tear itself apart, dividing between those friendly to Russia and those hostile. It is now dominated by politicians who increasingly cherish the memory of Ukrainian fascists who worked with Hitler whenever Hitler would allow it.

The book’s conclusion is:

“According to a friend of his, Gorbachev now grants that it may take a hundred years for democracy to take hold in his country. But he is proud that he was the one who opened the way. The great Russian intellectual Dmitry Furman called him ‘the only politician in Russian history who, having full power in his hands, voluntarily opted to limit it, and even risk losing it, in the name of principled moral values’.”

What’s so grand about a political system that does not work?

Systems with open multi-party elections generally rely on a body of experienced politicians whose deepest commitment is to keep the state and society in being. And who have a fair idea of how to do this: a process that involves unlearning many things that are valid for personal life. Making rules for communities of millions is a complex and confusing business.

Sadly, it is not the case that people given a free choice of elected representatives will always get what they want. They can force the champions of the ruling class to cloth themselves in the language of populism. Britain’s current Tory government does this all the time. So do the US Republicans, assuring everyone that tax ‘reform’ that will be an enormous new feast for a more-than-millionaire class will actually be good for ordinary people. And the nonsense often works, as it did in Russia. Putin’s poor politics are the best thing that can actually work in a messed-up society.

Copyright © Gwydion M. Williams

[A] https://www.lrb.co.uk/v39/n24/neal-ascherson/big-man-walking (subscribers only)

[B] Simon and Schuster, 880 pp, £25.00

[C] https://www.rt.com/news/413029-nato-gorbachev-expansion-promises/

[D] https://gwydionwilliams.com/42-china/communist-chinas-survival-after-the-tiananmen-crackdown/